ADDITIONS 2005

serial constructions and paintings by Kathryn Dain

Cambridge Galleries 2005

Curator Ivan Jurakic Essay by Ivan Jurakic TThe use of found objects in art has a century long history ranging from the Cubists use of daily newspapers in their paintings and collages to Marcel Duchamp’s appropriation of ‘readymades', including a bottle rack, bicycle wheel and infamously a porcelain toilet bowl. Artists affiliated with Surrealism further refined the use of found objects in assemblages, clever gestures such as Man Ray’s Object to be Destroyed and elegant sculptural hybrids, of which Meret Oppenheim’s Le Dejeuner en Fourrure (more commonly known as the Fur-lined teacup), remains a compelling example.

Repo Pop, 2003-05, 2000 popcans, acrylic, wood, 128" x 70"

Repo Pop, 2003-05, 2000 popcans, acrylic, wood, 128" x 70"

Repo Pop, 2003-05, 2000 popcans, acrylic, wood, 128" x 70"

Flow, 2004, 4.000 buttons, canvas, thread, 9.5" x 132"

147 Painted Squares 2002 media: acrylic on plywood 188" x 62"

49 Wrapped Squares, 1996, media: plywood, tissue, fabric, 2 miles thread 62" x 62"

147 Painted Squares 2002 media: acrylic on plywood 188" x 62"

Black & White, Baby Blue, Garnet, Spruce, Mauve, Navy, , acrylic on wood 8" x 8"

147 Painted Squares 2002 media: acrylic on plywood 188" x 62"

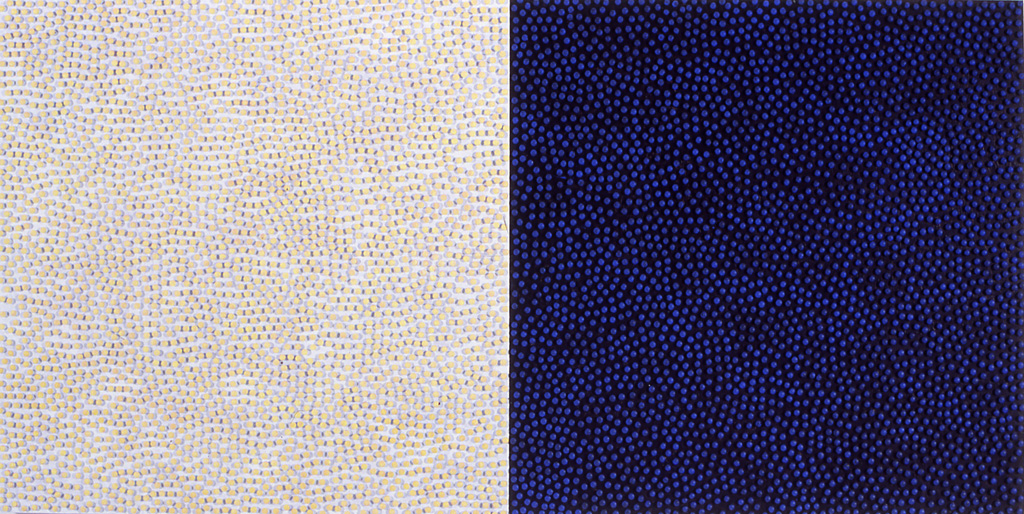

Plainsong (WB/WY, R - B/B), 2005 acrylic on wood, 5824 wooden furniture plugs, 64" x 32"

Plainsong (R/BG,W- WRB/WB,R), 2005 acrylic on wood, 5824 wooden furniture plugs, 64" x 32"

Plainsong (0(flourescent)/R - BR), 2005 acrylic on wood, 5824 wooden furniture plugs, 64" x 32"

Blue, 2003, 235 popcans, acrylic, wood, 48" x 48"

Red, 2003, 235 popcans, acrylic, wood, 48" x 48"

White, 2003, 235 popcans, acrylic, wood, 48" x 48"

Plainsong (O(fluorescent)R - BR), 2005 acrylic on wood, 5824 wooden furniture plugs, 64" x 32"

DDuring the post-war boom, found materials were increasingly incorporated onto the surfaces of paintings.At the time, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were championed as innovators for their incorporation of everyday items, including the remnants of advertising, thrift store materials and junk, in their work, a trend that eventually found its apotheosis in the 1960s with Pop Art.

IIn the wake of Pop, Minimalism proposed a radical reduction of forms and materials to bare essentials, often incorporating repetition and the use of grids as ordering systems. Operating parallel to their often more celebrated male peers, artists like Eva Hesse, Louise Nevelson and Agnes Martin produced influential bodies of work that often incorporated the use of found elements within the formalist underpinnings of their Minimalist-influenced art practice. All three became important role models to a generation of younger women entering art colleges and degree programs during the highly politicized 1970s and early 80s.

KKathryn Dain’s practice developed out of this context. Her work straddles the often contradictory lines between intuition and formalism. Her practice, while indebted to conceptual predecessors such as Hesse and Martin, builds on the foundations of her own journey as an artist and educator over the last 20 years.

AAs an artist, Dain uses paint in the same manner as she might choose to draw, sew, wrap or construct an artwork; each medium is a means to an end. The core of her mature practice is based on process and ritual. It is the repetitive and serial nature of her daily activities as an artist that defines her practice, not her choice of medium.

HHer artworks are experienced on multiple levels. First, the accumulative nature of her work becomes apparent as one recognizes that each is made up of hundreds, if not - thousands, of individual components. Second, the viewer must inevitably consider the amount of time and the level of handiwork involved in each. Third, an internal rhythm reveals itself within the composition over a period of time.

IIn Plain Song, a series of three diptychs affectionately nicknamed ‘dot paintings', each component creates a visual oscillation between the use of pure colours and the juxtaposition of seemingly randomly placed wooden furniture plugs - 2912 per square panel or 5824 per diptych. The contrast between surface and ground creates what Dain refers to as a neural colour. This neural colour appears in the gap between the different colours used, in effect creating a subtle optical illusion. Furthermore, patterns seem to emerge and recede, suggesting mazes, Celtic knots or unfolding fractals. The visual flow created when looking at each over a longer period of time has a meditative quality.

Plain Song WB/W,YR - B/B (2005) acrylic on wood, 32” x 64”

AA similar effect occurs in Repo Pop- made up of 2000 pop cans - and the series Red, White, Blue - featuring 235 pop cans per work or 705 in total. The repetitive patterns formed by the silver tops and bottoms of the accumulated aluminium cans contrasts with their crushed and repainted bodies to create an overall effect reminiscent of an abstract painting. The undulating patterns draw the eye through the artwork in a restless, yet controlled manner. Again, the seemingly random placement of cans belies an innate understanding of colour, form and arrangement that strikes an unexpected compositional balance.

SSpeaking with Dain, the idea of balance comes up again and again. Her work, whether painted, sewn or assembled, strives to capture and sustain a balance between randomness (chaos) and structure (order); between one colour and another, between one form and another, between the handmade and intuitive nature of the work and her methodical use of grids. As an artist, Dain strives to achieve a conceptual, psychological, even spiritual equilibrium.

FFor example, Flow is an assemblage made up of 4000 collected buttons that have each been hand-sewn onto a very long and narrow strip of canvas. This single piece illustrates the delicate balancing act required of Dain’s daily handiwork, her obsessive need to collect and to order, her intuitive approach to the selection of materials, and her affinity for fibre-based artwork. The piece also subtly addresses the artist’s expected role as a woman.

DDain’s artwork smartly reconciles her first degree in Home Economics, where she learned to sew, with her early training as a painter, allowing her skills and interests to develop into a conceptual practice overtime. Although the artist has a long association with fibre as a medium, wrapped cloth and paper being foremost in her inventory, her recent work opens itself up to colour and materials in a new way, without sacrificing the qualities inherent to her work. Her best work borders on an obsessive compulsive disorder that has been refined into a daily ritual one might call an act of creative accretion. On the surface, there is punch-clock aspect to the repetitive labour involved, but her process is never detached. Like her predecessors, Dain maintains a formal allegiance to Minimalism but her work is never cold, nor sterile, it remains warm and handmade.

AAssemblage remains an attractive proposition to many artists because the items used share a common visual vocabulary recognizable to a broad audience. Conversely, this can also be disarming because of the often unexpected or purposefully crude nature of the results, hence the derogatory term junk art. The use of found objects also encompasses a very down-to-earth reality for many artists, namely economics: the materials used are often readily available, cheap to purchase in bulk or free. For instance, most of the pop cans Dain used were found in her Brantford neighbourhood, many excavated at winter’s end when the snow and slush receded to reveal a bounty of available material.

IIn many ways, making art out of detritus is an accurate, if somewhat unflattering portrait of the modern world we live in. Waste accumulates along the curbside, as surely as bric-a-brac is packed into dresser drawers and boxes or nuts and bolts end up accumulating in coffee tins, We are a culture of packrats. Dain’s practice makes art out ot our very human habit of collecting, storing and reusing.

Ivan Jurakic, Curator